The commonest form of worship in a Buddhist temple is an offering of flowers. The flowers are cupped in the palms of the two hands and offered at chest level to the Buddha. This act of worship is carried out in the shrine room where an image of the Buddha is always kept, or at the stupa or Bodhi tree which are associated with the enshrinement of the Buddha’s relics and His enlightenment.

The devotees then recite the invocatory Pali stanzas: “With these flowers, I revere the Buddha Through this act of merit may T achieve release; And as the flowers wither away, even so does my body turn to dust.”

Flowers express the transient nature of life, the impermanence of our feelings and actions. This is a basic tenet of Buddhist doctrine. They also symbolize righteousness, and remind devotees that they must try to make their lives just as chaste and beautiful. The fragrance of the flower they offer is yet another reminder of the Buddha’s words that “the sweetness of virtue far excels the fragrance of flowers.”

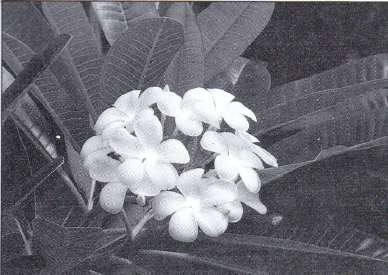

The most common flower offering is the fragrant frangipani or araliya (Plumeria acutifolia). This is why the tree on which it grows is familiarly known as the “temple tree”. It comes in a range of colours from white, through shades of pink to deep red and yellow. But it is the white flower that is most favoured.

White signifies purity, and the white flowered variety is consequently widely planted by the Archaeological Department in ancient pilgrim sites, and by the priests in Buddhist temples, to provide even the poorest devotees with this means of worship.

Raven-Hart, the author of Ceylon, History in Stone, has an interesting anecdote in this respect. When he v1as visiting the Ridi Vehera (Silver Temple) near Kurunegala, at a time when pilgrims were leaving their offerings of araliya flowers on the altars, one of the pilgrims asked him whether he would like to offer flowers too.

“I have given my offering,” the pilgrim said, “but I shall send my son to the trees to bring some flowers for you.”

When Raven-Hart demurred, saying something about the trees being temple property, the pilgrim replied: “But of course! That is why the temple plants the trees, because no one must be denied the opportunity to offer flowers.”

He continued: “lf the flowers underneath have already been picked, and you are not tall enough or nimble enough to get the flowers at the top, then just put your hands together, look at the flowers above and dedicate them to the Buddha. It’s quite all right.”

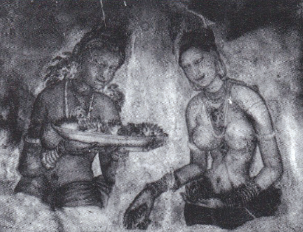

In fact, there is no need for devotees to go specially to a shrine room to offer • flowers to the Buddha. They can do this anywhere with merit so long as they contemplate His great virtues while doing so. There 1s some doubt as to whether the common-or-garden temple flower araliya was introduced by the Portuguese from India in the 16th century, or whether it was of earlier origin. Those who favour an earlier origin point to the flowers carried by the “Ladies of Sigiriya” (SAD) which look remarkably like araliya. The consensus of opinion, however, is that the flowers appearing in the Sigiriya frescoes are waterlilies, or mane/. The strongly scented star-like white flowers of the jasmine (Pichcha or Jasmin um Sambac) are also popular temple offerings. These flowers were held in high esteem by Sinhalese royalty. The Mahavamsa or old Chronicle records that King Bhatikabbaya (20BC-9AD) had a plantation of flowers covering eight miles, and that on a certain religious festival he completely covered the huge dome of the Ruwanwelisaya in Anuradhapura with sweet scented jasmines, studded amongst which were other flowers.

Robert Knox, an English captive in Sri Lanka in the 17th century and author of An Historical Relation or the Island or Ceylon reports that King Rajasinghe II of Kandy “had a parcel of jasmines brought to him every morning wrapt in a white cloth hanging from a staff” for his daily offering to Buddha.

Flowers are often available at stalls near temples.

The scented white lotus or olu ( elumbium nucifera) is another popular offering. The flowers are picked as buds and carefully opened before they are offered at the temple. The very act of opening the petals is a symbolic reminder of our spiritual reawakening. The lotus grows in the shallow water of a pond or lake, the roots in the mud with the leaves floating on the surface of the water. The lake or pond represents the physical world around u providing material sustenance. The flowers borne in the air above the water are symbolic of the blooming of our consciousness of spiritual evolution.

In the words of the Dhammapada (Buddhist doctrine): “From the mud and slush there blooms the lotus, fragrant and pure. Likewise in the midst of those attached to this world, with their eyes dazzled by the glamour of material pleasures, there comes into being the disciple of the enlightened one, who by his wisdom radiates the truth and outshines them all.”

The fully blossomed lotus signifies the Enlightened Guru (teacher) or a person who has received “divine” illumination. The gradual unfurling of the petals of the bud from the first streaks of dawn to the fully opened flower when the sun is at its height is symbolic of that conscious evolution from material man to spiritual man. Devotees believe that the enlightened nature of the Buddha is within their own real natures to achieve. And every time they offer flowers, they dedicate themselves to that ideal.

The Ladies of Sigiriya carried flowers.