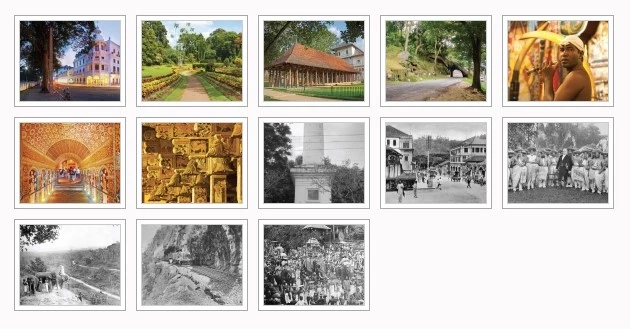

If cities were people, Kandy would be the grand dame of Sri Lanka: gracious, stately and still very beautiful. Sheltered in a natural fortress of thick tropical forest, unruly rivers and steep mountains, Sri Lanka’s hill capital commands a position of esteem as the centre of the country’s Buddhist heritage and the last bastion of the Sinhala monarchy. Kandy’s religious and historical significance was endorsed by UNESCO in 1988.

Words Daleena Samara Photographs Rasika Surasena

Naturally lovely, the city spreads across 27 square kilometres of verdant valley at the foothills of mountain ranges, 465 metres above sea level in Sri Lanka’s scenic Central Province, and 115 kilometres from the capital city of Colombo. The grand dame has experienced the fascinating ebb and flow of fortunes. The city has been created, destroyed and recreated. For a time, it was a fortress for the country’s monarchs. It lives today as an important World Heritage site and centre of Buddhism.

The 142-acre Peradeniya Botannical Gardens on the outskirts of Kandy is where, as history has it, the city began as Senkadagalapura Siriwardhana Maha Nuwara (“great city of Senkadagala of growing resplendence” in Sinhalese). However, history records its first roots in the nearby city of Gampola, 14 kilometres away, where King Bhuvanekabhahu established a base in the early 14th Century. At the request of his powerful chief minister, Senadhilankara, the king donated extensive tracts of land near Peradeniya for the new Lankatilaka Vihara.

Records show that King Wickremabhahu III (1357-1374) established a residence by the Mahaweli River, on ground that is now the Peradeniya Botanical Park, from where he ruled the sub kingdom of Kandy, under the Kingdom of Kotte. He was succeeded by King Sena Sammatha Wickremabhahu (1469-1511), during whose rule the Kandyan Kingdom had a short-lived dalliance with independence. He was succeeded by Jayaweera Astana (1511-1552), followed by Karaliyadde Bandara (1551-1581). They were the first kings of the minor kingdom of Kandy. The 1500s were marked by the arrival of the Portuguese explorers who sought a monopoly on the cinnamon trade. They were followed by the Dutch and then the British, who ruled the country from 1658-1796 and 1815-1948 respectively. All were greedy for the country’s spice bounty. The Portuguese who arrived in 1505, remained in the country until 1658, gradually taking possession of much of the country’s coastal regions. Kandy remained impregnable.

The name Kandy was a British improvisation of the Portuguese ‘Candea’ for Kanda Uda Rata (‘land on the mountain’ in Sinhalese). The arrival of the Europeans put the coastal kingdoms at risk, and Kandy gained ground as a naturally fortified base from which to fight off the invaders.

The British extended the land and designated it the Peradeniya Botanical Gardens

The king’s residence in Peradeniya was destroyed by the British who took control of the hill capital in 1815. But before that, King Rajasimha II (1608-1687), had declared the grounds a royal pleasure garden. The British extended the land and designated it the Peradeniya Botanical Gardens, for the cultivation of indigenous flora. It continues to thrive today, home to over 4,000 species of trees and other flora, and wildlife.

Gannoruwa across the river from Peradeniya was a common route of invading and defending armies. Balana presents a bird’s-eye view of the surrounding lands. The Portuguese made three failed attempts to conquer Kandy. The bloody Battle of Gannoruwa was their third and final. Led by the Portuguese Captain General Diego de Melo de Castro, the colonial army marched into Kandy but found a ghost town. So they ransacked and set fire to the city, before retreating through Gannoruwa. It was a trap. As they camped on the river bank, they were set upon by king and his army. The general and his troops died in the battlefield, now the grounds of Ranabima Royal College.

King Rajasimha II gained notoriety for imprisoning a young Englishman on the Island, Robert Knox, a sailor whose ship had drifted ashore in Sri Lanka. The king kept him in Kandy for 19 long years, allowing him every freedom except that of escape from the hill capital. He eventually crept away into Dutch territories and jumped ship to England.

It was King Wimaladharmasuriya I (1592-1604) who established the city’s signature monument—the Temple of the Tooth (Sri Dalada Maligawa), securing its position as the capital. The king started life as Konappu Bandara, son of Kandyan Buddhist nobleman Weerasundera Bandara, who crossed swords with King Rajasimha I, son of King Mayadunna of Sitawaka. The king had converted to Hinduism. Fleeing from him, Konappu Bandara sought refuge with the Portuguese who baptized him Don Juan Dharmapala. However, when the Portuguese attempted to gain control of the hill capital by installing a Sinhalese princess convert, Dona Catherina, as their puppet queen of Kandy, he surprised them by secretly marrying her and securing the throne for himself. Reconverting to Buddhism, he consolidated his position by bringing the sacred tooth relic to Kandy.

Today the temple complex is an extraordinary juxtaposition of palace and temple

The sacred relic, the wisdom tooth of Gautama the Buddha, was smuggled into Sri Lanka from Kalinga by Princess Hemamali and Prince Dantha of Orissa, hidden in the princess’s hair. Venerated by Buddhists across the world, the relic is enshrined in a golden casket in the Dalada Maligawa (Temple of the Tooth). The original two-storey temple no longer exists. Successive kings have added to the structure. King Wimaladharmasuriya II (1686-1706) built a three-storeyed temple, his son and successor, King Viraparakrama Narendrasinha (1706-1738) replaced it with a new two-storeyed structure. Later kings added more improvements. The octagonal pattirippuwa and the Kandy Lake were added by last king of Kandy, King Sri Wickrema Rajasinghe (1797-1814).

Today the temple complex is an extraordinary juxtaposition of palace and temple, in keeping with the creed that the rightful ruler of the land has possession of the relic. The first palace on the site was built by King Sena Sammatha Wickremabhahu.

The lake had special baths for all the king’s wives. It also holds dark secrets.

Although Kandy fell a few times, neither the Portuguese nor the Dutch succeeded in wresting the city from the Sinhalese. The British had better luck. The straw that broke the Kandyan back was infighting. The court of the last king of Kandy was fissured by distrust, and so the nobles collaborated with the British on ways to dispose of their tyrannical king. The Kandy Convention signed on March 10, 1918 set out the rules of engagement for the British. However, once signed and the troublesome monarch and his wife exiled to South India, it was time for betrayal. February 15, 1815 marked the session of the Kandyan provinces to the British. The Union Jack was hoisted in Kandy and British dominion of the interior was announced with a royal salute from the cannon.

The British left Sri Lanka an invaluable public transportation system: the railways. Service to Kandy began in 1867.

The British mark on the city is evident in its infrastructure. Schools were established such as: Hillwood College, Trinity College, Kandy Girls High School and Kingswood College, which continue to be educational institutes today. Queen’s Hotel started life as the governor’s residence. The British left Sri Lanka an invaluable public transportation system: the railways. Service to Kandy began in 1867.

Under British dominion, the fertile paddy lands on which the Kandyan farmers cultivated the country’s staple, paddy, were redeployed for the cultivation of cash crops such as tea and coffee. The result was the lucrative tea trade for the British and a lasting heritage of delicious tea for Sri Lanka.

Today, Kandy is a city of peace, synonymous with Buddhism. Every year, during the month of July or August, the Kandy Perahera re-enacts the ancient traditions of the city, with a dazzling procession of costumed elephants, dancers and more. The centerpiece is of course the sacred relic enshrined in a golden casket, tenderly carried on the back of a magnificent tusker. The grand dame of Sri Lanka smiles a message of peace.