Rodney Jonklaas

On the flights to India, the title of this piece flows sweetly from the lips of Air Lanka inflight crews.

The Guinness Book of World Records has it that Sri Lankans are the least meat-hungry of all nations, with the carnivorous Uruguayans in the lead. This does not mean, of course, that most of us are vegetarians. There are lots of novel chewy proteins apart from meat, or shall we say beef?

Lots and lots of fish, and increasingly fowl, enrich the staple diet of rice for Sri Lankans. 99.9% of us, I am certain, are rice eaters. And what goes with rice, we all maintain is veg. No meal worth devouring in green Sri Lanka is sans some sort of vegetable.

With a wide variety of climatic zone, vegetables are grown to suit them. Perhaps a Guinness researcher can come up with some kind of a record concerned with the variety of plants and their component parts which constitute vegs consumed by Sri Lankans. This article can just about touch on some of them, excluding, of course, the very obvious ones. You know, carrots, beetroots, leeks – those kinds of vegetables…

You can bet that every single minute of the day, and for a fair chunk of night as well, hundreds of mouths with fine white teeth are chewing away at vegetables in Sri Lanka. And every single home, however humble, will feature some kind of a vegetable at mealtime. Every single provisions shop, boutique, market, fair, supermarket – any place involved with food-depends on vegetables for its survival.

I don’t mean cereals, staples or sweet (sometimes sour) fruit in the dessert or afters sense. I mean veg. And this can be fruit, shoot, flower or root or parts of thereof.

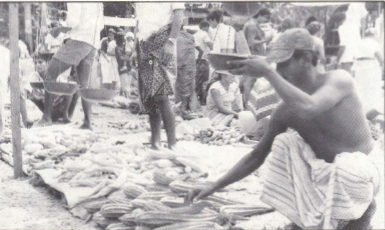

The best places to gape at vegetables are fairs and village markets. Modern supermarkets have them, but seldom if ever the really traditional off-beat ones with equally strange names. I mean, you just will not acquire kera koku at any of Colombo’s plush fooderies. But just meander swamp-wards and ask an eager housewife trying to nourish her menfolk and she’ll produce a handful of prehistoric-looking curved shoots of the ever-so-common giant fern botanists recognize as Acrostichtum aureum. This unusual food could well be compared to the much-esteemed asparagus tips we all know and pay dearly for. But the comparison is feeble. The marsh fern grows into immense bushes that could exceed three metres in height and conceal a small party of duck-hunters. Land reclamation in lowland swamps often resorts to small bulldozers and tractors to uproot these vegetable sources.

And not to be outdone, where it is drier inland, many an enterprising housewife obtains the delicious madu-koku the tender shoots of the cycads for a very special vegetable curry.

Whereas in milder climes watercress is a favourite ingredient for dainty sandwiches at tiffin, our veiy own ‘gotukola’, the delicious rounded leaves of a marginal herb growing by paddy-fields, makes one of the nicest ‘sambols’ ever. The botanists call these Hydrocotyle and Centella.

When is a fruit a fruit and not a vegetable?

It all depends on how you eat it. In Sri Lanka not just fruits but also nuts (and that includes groundnuts, of course) are regarded as vegetables. And, as we all know, currying just about everything of vegetable origin is the universal way of eating them. So adept are the ladies who please us all with their culinaiy prowess that many a human carnivore can be fooled (especially after some. of the brew that cheers) into engulfing chunks of meaty-looking and tasting stuff that never came off an animal.

Of them, the very tender jak fruit called ‘polos’ takes pride of place. Chunks of polos with the right condiments can rival in taste and texture such delicacies as veal and venison. Little wonder that nearly all the canned polos are whisked off to Canada, Australia and England to delight Sri Lankans resident there. The locals don’t really mind. In season the great jak trees literally erupt polos off their stems and one wonders how any pass this stage, turning into ‘kos’, which is also a great veg dish embellished with nuts, finally graduating to ‘varaka’ or ‘vela’, the sweet juicy ripe jaks with their overpowering scent. There is a saying which goes like this, illustrating fervently the Sri Lankan passion for ripe jak: Discretion may be the better part of vela, but give me varaka anytime…

Real vegetables which are never eaten ripe, nor raw, are many in variety. Only cooking with a firm hand can convert those strange corrugated gourds called ‘vetakolu’ into a curry. But the appealingly bitter ‘karawila’ can also be eaten crisp-fried sometimes as snacks with arrack or toddy.

The bawdy rural humour has it that small plantations of snake-gourds grown as creepers on wooden trestles must be kept covered on all sides lest too many eager maidens ogle them. Well-grown (and protected!) snake-gourds can exceed a metre in length. Boiled, cut into convenient lengths, then stuffed with something meaty and spicy, they can put the ubiquitous doughy Chinese rolls to shame.

In the North and also in other very drier areas, growing on delicate-leaved and slender trees, are long, green pods -the ‘murungas’. I can eat ‘murunga’ curry every day of my life, believe me. The unforgettable flavour of the flesh and tender seeds can fool a gourmet when you use it in a daintily buttered roll of white bread, because fresh asparagus tips are the nearest to these. And we just cannot get decent fresh asparagus tips in Sri Lanka.

One of the delights of rural Sri Lanka is a dish of steaming, boiled light yellow manioc, or tapioca, to be pounced on and swallowed with some red-hot chilli sambal and generous helpings of fresh, grated coconut. Few Sri Lankans have not tried it and loved it, and if you haven’t, make it a point to organize some. This tremendous feast is best taken at tiffin time, preferably when it is cool or on a wind-swept hillside under a sighing tree.

Almost as nice eaten this way is sweet potato, but some of us must shy away from sweetness as age comes on. Manioc is for all ages and, no doubt, is ageless. Quite a few of our housewives buy baked beans but, although they are eaten cheerfully enough, wonder as to what has happened to the skins of the pods that bore them. Over here. more attention is paid to the whole tender bean as curry or veg with meats than the seeds alone. All sons of beans of all shapes and sizes get involved in curries and sambols; only a few end up boiled, limp and soft to set off meats or garnish them. From the slender, convoluted ‘makral’ along with green and butter-beans and the frilly winged bean, a respectable select.ion is available in most markets. In most parts of rural Sri Lanka well away from crowded towns and cities, many an enterprising and humble housewife can provide her kith and kin with inexpensive and nutritious veg all the year round. And it is often the done thing for the young girls and boys to go out foraging, getting them for nothing from where they grow. One can well imagine a mother asking the kids to stop fooling around and collect some leaves, tender fruit, yams and shoots for lunch.

They would saunter out into their garden, perhaps a neighbour’s peer through hedges, splash through paddy fields and yank out a plant here and there and then come home with a nice assortment. You can still do this in many parts of Sri Lanka but not in many parts of the developed world.

A variety of country vegetables in a stall at an open-air market. (Suresh de Silva)