Lasanda Kurukulasuriya

It should come as no surprise that the item most sought after by tourists shopping in Sri Lanka today is jewellery. Gems and precious metals have lured people to the orient from time immemorial. The smithying of gold and silver and the making of gem-studded ornaments are crafts that were practised with a high degree of skill in medieval Lanka. Many a tale is told of the remarkable work carried out by these artisans. The story goes that the famed goldsmith Ratnavalli Navaratna Abharana of Nilavala once set a gem in the big toe nail of king Kirti Sri, while he was asleep, without waking the monarch! Robert Knox in his colourful chronicle of captivity under the Kandyan king relates how Raja Sinha would …. “try his guns, and shoot at marks, which are excellent true, and rarely inlaid with silver, gold and ivory. For the smiths that make them dare not present them to his hand not having sufficiently proved them.

Accounts of the life and times of the Kandyan kings abound with descriptions of the grandeur of the court and the pomp and pageantry which accompanied ceremonial occasions. On state occasions the king would appear in splendid attire, decked with jewellery, bearing a jewelled cane. The throne was plated with gold and decorated with gems.

According to ancient chronicles, offerings of gems and jewellery were made to the Dalada Maligawa (Temple of the Tooth Relic) and other temples. It is in the vihares and devales – the Buddhist and Hindu shrines – in fact that some of the finest examples of workmanship can still be seen, in the form of gold and silver plating, damascened door locks, handles, key-plates etc.

The wearing of jewellery was confined to royalty and a few noblemen and their families, who may have been gifted with it by the king as reward for some special service rendered. Unlike in modem times, it was equally the privilege and fashion of men, as of women, to wear chains, pendents, girdles, rings etc. Knives or swords ornately inlaid or overlaid with silver, gold or ivory also formed part of the ceremonial attire of the great chiefs.

In the hierarchy of craftsmen, the goldsmiths and silversmiths belonged to the ” higher” category, together with painters ivory carvers, wood carvers and brass repoussers. They held large extents of land endowed to them by the tare in return for their services, and in fact vied with the noblemen for the king’s favour.

Though the art has degenerated since those days, there still remains in Kandy a few families of smiths who continue to practise their craft using traditional designs and methods. Danture, Madawela, Embekke and Nilavala are some of the villages where such work is still done.

Very little traditional jewellery is made by them in gold today, because of the prohibitive cost of the raw material. It is mainly silver ware that is available much of it being sterling silver, the alloy containing 92.5%.

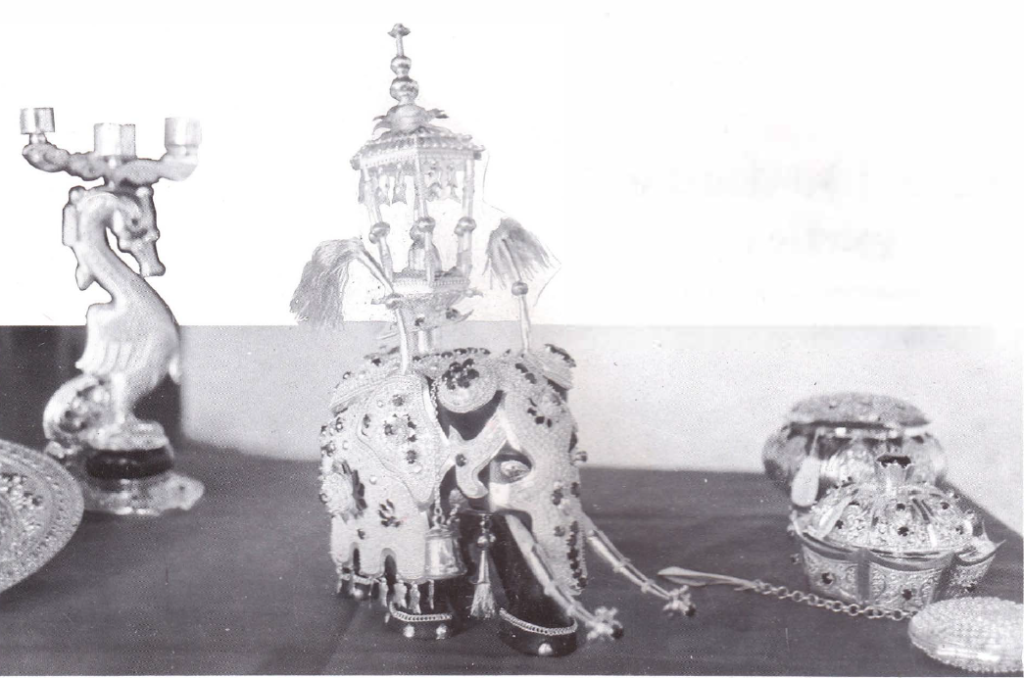

The tourist who picks up and admires an ebony elephant caparisoned in silver, would little suspect the amount of time and labour spent on its creation. Such patient and attention to minute details does the work entail that, watching the process in the musty, smoky workshop of the smith, he or she would probably be amazed that such work is carried out at all.

The colour of the silver which is bought in sticks is a dirty grey. The sticks are beaten flat and soldered into pieces of the required shape for the elephant’s covering. It is then decorated with motifs made out of thin strips and very fine wire-work in silver, which are also soldered on to the plate.

The wire is made by drawing the silver through a series of holes in a flat metal stick, each smaller than the other. The fine thread that is finally obtained by this laborious process is wound round a long pin, which is later removed, leaving the thread in the shape of a thin spiral. The same process is repeated with the spiral which is then cut into fragments which resemble minute flowers. A mass of these flowers is soldered on to the front piece of the caparison, using a greenish gum made with crushed olinda seeds. Larger flowers made out of thin strips of silver are used to decorate the rest of the covering.

The silver beads used as centres for the smaller flowers are formed by heating chips of silver wire in a crucible made of graphite and clay. Some handfuls of burnt paddy-husk are added to prevent the chips from sticking together.

The soldering is done over a primitive type of gini-kabala ‘ – an earthen vessel filled with coconut!:bell charcoal embers. The flame is directed to the area that needs to be soldered with the help of a blow-pipe. After soldering, the metal is dipped in sulphuric acid and heated in order to whiten it. Finally, dipped in silver and set with garnets, tourmalines and amethysts, the elephant’s attire is ready. Placed upon the carved ebony, the product is metamorphosed into the delectable souvenir that is carried away to distant lands.

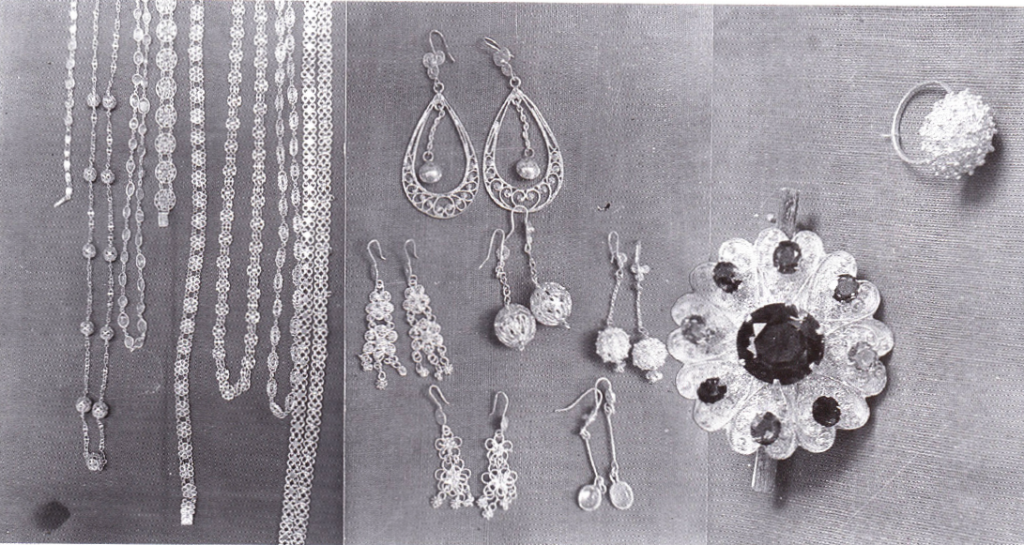

Similar processes of soldering and decoration are used to make items of silver jewellery, parts of which are also sometimes hammered against a mould so that a design surfaces, or else delicately engraved. Although there is much that is distinctly indigenous in the craft, designs and techniques in jewellery making reflect strong South Indian influence. Many of the original artisans who served the court were imported from South India. The origins of the designs of chains, for example the ‘pethi malaya’ (petal garland), ‘gedi malaya ‘ (fruit garland) and so on, can be traced to the real garlands of flowers worn at Indian festivals.

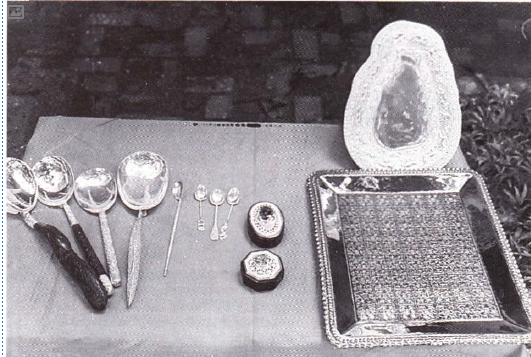

Spoons big and small, and trays of many shapes and sizes are available for sale at the KAA.

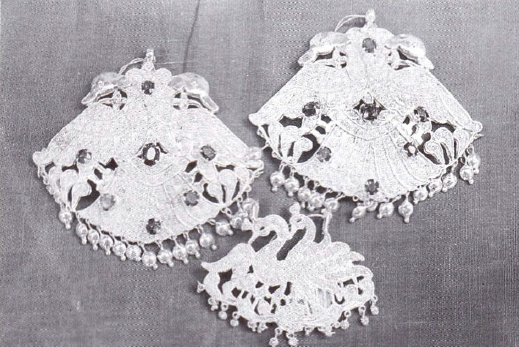

Padakkam or pendants studded with gems fashioned in the traditional Hansa Puutuwa motif.

An elegantly carved silver tea set with a matching tray. (Suresh de Silva)

Items like trays, tea sets and caskets are wrought and ornamented in much the same way as sheet-work in brass -except that they are repoussed many times over.

The showroom of the Kandyan Art Association beside the Kandy Lake, displays

a large variety of the best examples of silver craftsmanship found in Sri Lanka today. The filigree drop earrings intricately carved or studded with precious and semi-precious stones, rings, brooches and sari-pins sometimes reflect the Kandyan influence in the designs. The silver padakkams (pendents) with designs of swans (Hansa Puttuwa) are an essential part of the Kandyan woman’s ornaments and come in different sizes studded with gems. The chunky bracelets worn by the peasant women as well as the rich are also a compulsory item included in a Kandyan woman’s dowry.

Among the better known souvenirs in silver for Sri Lanka are trays. These come in many shapes and sizes. There are trays shaped like Sri Lanka with floral designs beaten along the edge. The large circular trays have the motifs usually seen on moonstones engraved all along the borders and geometric floral patterns in the centre. Delicately carved trinket boxes, spoons large and small from the deep rice spoon to little coffee spoons have traditional motifs on their handles, and are often inlaid with wood. Whether filigree or damascene the silver craftsmen of Kandy show a rare versatility of style and a sure understanding of the craft.

Silver chains, earrings, rings and brooches in traditional designs, still very much in vogue. An indispensable part of a woman’s jewellery box.

( Suresh de Silva)